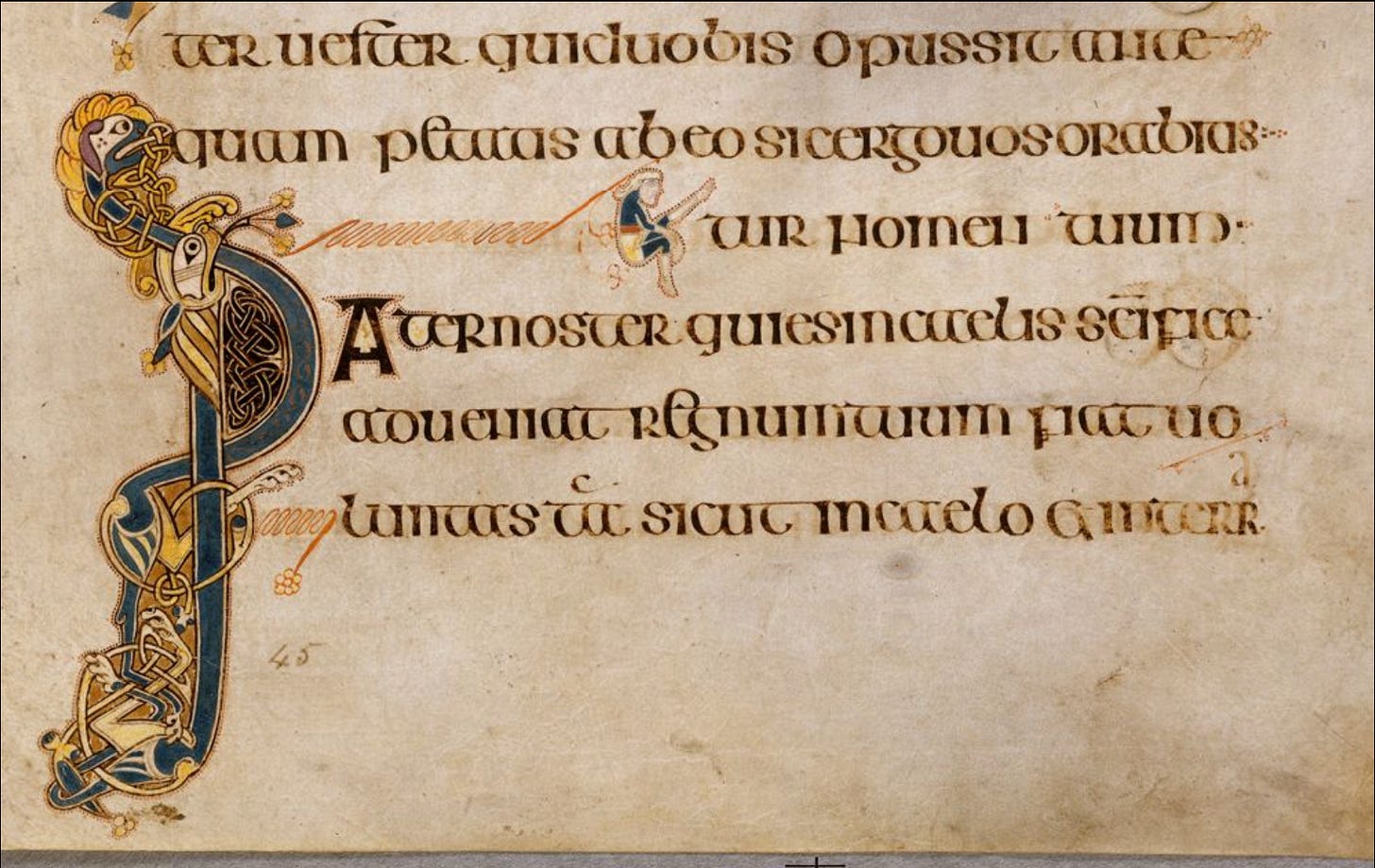

I recently took a certification course on Medieval Paleography, or, in other words, how to read the Latin in anything from the gloriously illuminated Book of Kells to the most ornately cramped Gothic Blackletter, which makes every page look like its yelling at you in the world's fanciest German.

Aside from the obvious pros of this work, like spending hours listening to Gregorian chants and swearing over letterforms that look exactly like other letterforms, the most beautiful thing about working with medieval manuscripts is the thinning of the veil that happens between past and present. You can see where the monk got tired. Where someone else came in and furiously corrected babtism to baptism. You can spot the daydream marginalia, the painstaking Celtic knotwork—the random snail artwork, and the doodled nuns picking genitalia off a tree. You can learn a scribe’s handwriting.

These books create thin places in time.

And once you’ve learned to recognize that shimmer between worlds—between scribe and reader, between chant and silence—it’s hard not to see it everywhere.

The Gospel of Luke reads like that.

It's not a ledger, not a courtroom transcript, not a news article, but a manuscript filled with marginalia and firelight. It's a gospel of interruption and ache, where the sacred presses close in kitchens and borderlands and bread still warm from the fire. It doesn’t argue for salvation but reveals it like ink slowly coming visible under a candle’s heat.

The Gospel of Luke paints a portrait of Jesus as a fringe-walker.

A threshold.

A thin place on legs.

People forget sometimes that the gospel books are not intended to be harmonized into one account or mined for who did what where. They are intended to give us a specific portrait of Christ. The focus of each author is slightly different. Luke is unique: he is very focused on the marginalized, he highlights women more prominently, he’s likely writing to Gentiles or Hellenized Jews as he includes stories of faithful gentiles who Jesus heals or praises for their faith. My argument here, if one can make one of those in a Substack, is that Luke is very Celtic in vibe. Luke’s Jesus goes to the borders to find the excluded. He re-integrates people into society. He sets a lamp on the path of the sacred, and Luke highlights the folks in the crowd who manage to spot it.

And Jesus tears the veil.

Jesus our Anamchara, have mercy. Christ have mercy. Lord, our High King, have mercy. Lord have mercy. Jesus our Druid, have mercy. Christ have mercy. - Celtic Kyrie

He is not merely a teacher or a prophet, but a living threshold: a convergence of heaven and earth, seen and unseen. His baptism splits the sky (Luke 3:21–22). The sky doesn’t just brighten—it rips. Heaven opens, the Spirit descends, and the voice of God speaks love over him. This isn't spectacle. It's thinness: a declaration that the divine is near.

His transfiguration floods the mountaintop with unearthly light (Luke 9:28–36) His face changes. His clothes catch the light of another world. The voice speaks again. Peter tries to hold it, tries to build something to contain the thinness. But glory doesn't stay boxed. We are in what John O'Donohue calls “revelation time”—he points out that to reveal is also to re-veil. A glimpse of understanding. The glory flickers and moves on.

But when Jesus dies, the sun darkens and the veil is torn. Not a crack in the fabric of religion, but a rip in reality itself. The division between God and us--that old border--gives way in his very body.

Jesus holds open the door of thinness with his self.

Thin places don’t disappear when Jesus does. If anything, Luke shows us that they multiply. The veil doesn’t seal again. The sacred begins to show up wherever presence is offered, wherever exile is undone, wherever someone is seen.

Jesus, in Luke, is the site of thinness. Community is the carrier of it.

(Heck, Luke wrote a whole second book about it!)

Religion and Christianity is fraught right now. The church is buckling under Christian nationalism, people co-opting the story of Christ for commercial and political gain, and people who are more interested in letting hell in than heaven.

As a historian, let me say first: this is not new.

However, as weary as I become, what keeps me here are the thin moments. When resource meets need like it's kismet. When a woman who crochets fixes my foster kid's blanket, restoring it from shreds to whole. When my oldest goes and finds one of the women in our church who lost her spouse last year and makes sure to give her a huge hug every week. When a wandering traveler shows up to our church and leaves with train fare for St. Louis to see his grandma, a ride to the station, and a stack of tupperware of food from fellowship.

Thin places. Heaven carried by presence.

Sometimes it’s quite literally the only thing that keeps me in the church at all.

In Luke, thin places are not reserved for mountaintops or mystic caves. Instead, they erupt into ordinary places with disruptive grace. Heaven is not far; it is fraying into the world through him. In the Celtic tradition, thin places are not made sacred by our rituals but revealed by presence. Luke’s Jesus is that presence.

I don’t stay in the church because I agree with everything that happens inside it. I stay because the veil was torn—and someone has to help hold it open.

Eriugena once wrote that Jesus is the threshold incarnate. The sacred seam between spirit and flesh, death and life, exile and home. And if that’s true, then what we do now, when we love to the margins, when we make casseroles and fix blankets and remember names, that’s not filler. That’s the seam being stitched again.

Thin places are not escape hatches from the world; they are points of reentry, where heaven insists on being here.

So we keep holding the door open. Just wide enough for God to slip through.