Beneath Our Feet: The Periodic Awakening of Cicadas

Tracing the Historical and Ecological Journey of America's Loudest Insects

Underneath the feet of those of us in the middle United States, insects older than my teenager are getting ready for a wedding and a funeral.

Seventeen years ago, in 2007, mother cicadas mated, then nibbled notches into the twiggy new growth of trees. There they laid pearly, oval eggs in clutches of twenty. Using her sharp, dart-like ovipositor, she continued depositing her eggs in these slits along her chosen branch, working as silently as her male counterparts are loud.1

She laid 400-600 eggs, and then died.

Her children emerged six to ten weeks later. White nymphs like bleached ants emerged from those eggs. Moses Bartram describes the event in 1766:

"The young that were hatched in the twigs ran down immediately to the earth, and entered it at the first opening they could find, which they searched for eagerly, as if already sensible of danger, by being exposed to the light of the sun...I have not yet been able to discover the full depth to which the little animals descend. Some, I have heard, have been found thirty feet deep. I myself have seen them ten."2

It's also interesting to note that cicada nymphs go deeper into the ground, but they don't often move much horizontally. So if you see cicadas emerge in bare ground, you are likely seeing the ghostly remnants of trees long gone.

Driven by a molecular clock lodged somewhere deep in the nymph's prehistoric brain, the cicadas ascend to the top layers of soil in the final year of their life, waiting just eight inches below the surface. In the weeks before they emerge, they are already busy extending the tunnels they will use, the culmination of nearly two decades of patient waiting. Sometimes they build mud turrets, sticking out a few inches above water-logged ground.

Driven by a molecular clock lodged somewhere deep in the nymph's prehistoric brain, the cicadas ascend to the top layers of soil in the final year of their life, waiting just eight inches below the surface.

And then, when the soil reaches 64 degrees, the earth awakens.3

Cicada nymphs, en masse, climb out of the ground and into the tree canopy for the final brief weeks of their life. This synchronous wave of life overwhelms predators, of which there are many, with their vast numbers. Their ancient drone becomes the backdrop of one historic summer.

Love them or hate them, cicadas are coming.

The cicada is an insect in the order Hemiptera, an order of True Bugs. They have prominent eyes, short antennae, membraneous wings, and a unique section of their abdomen called a tymbal. The tymbal muscles oscillate stiff rib-like structures below their folded wings, creating a buzz then amplified by a special tymbal cavity.4

The resulting noise from the male cicada is something between a rattle and a whine that can get up to 90-120 decibels, a sound in the same auditory neighborhood as a motorcycle or jackhammer.5

They also gather in chorus centers in trees, so imagine a tree full of jackhammers.

Male cicadas also have the handy ability to crumple their own eardrums, rendering them functionally deaf during their call.

Lucky for them.

Cicadas appear on every continent save Antarctica, with over 3000 species to the family name. Most are annual cicadas or what's called the "dog-day cicadas," who come out every year in the hottest part of summer. But Periodical Cicadas are unique to North America. Emerging in broods in prime number periods of 13 years (like in the southeast) and 17 years (like in my home, Illinois), the cicada is history's own bug. It's an alien that surfaces every decade and a half or so, just to see how the topside world is doing.

They are the subject of myths and folklore, are fossilized in both amber and poetry, and send a "resource pulse" throughout the whole ecosystem, defined as episodes of resource availability that are rare, intense, and brief.6

They are symbols of resurrection, they survived the dinosaurs, and they saved the people of the Haudenosaunee nation from certain death.

In short, cicadas do a lot with the little time they have.

Let's get into it.

Cicadas have a long pedigree of ancestry. Appearing in the fossil record in the Upper Permian and Triassic periods, the proto-cicada had wider, butterfly-like wings, no droning call, and lived when the separate continents we know today were fused into the super-continent Pangaea.7

Cicadas made it through the Great Dying of the Permian extinction when volcanic activity shrouded the world in ash, outlived the mass global extinction of the dinosaurs, and they'll probably outlive us too.

Modern Cicadas are divided into two groups, hairy cicadas (Tettigarctidae) and singing cicadas (Cicadidae). While there are only two species of hairy cicada, they preserve the old communication style of the prehistoric cicada. Hairy cicadas have no abdominal tymbal and make no rattling whine, instead, they produce vibrations with their legs and send them through mediums like branches and leaves.

The singing cicada is far more common. Boasting 3,000 species in every corner of the world, most communities from ancient times to the present are familiar with the song of the cicada. It is hypothesized that the cicada’s feeding adaptations and body structure changed in response to the profound structural change that vegetation underwent through the Cretaceous period, as new types of forests emerged and plants evolved flowers.

The strategy of the cicada nymphs was to go underground to drink the xylem, a nutrient sap that flows in the roots of trees. Some entomologists believe that the DNA of periodic cicadas allowed for longer and longer time underground as they did their growing and molting below given fewer predators.

Entomologists believe that the periodical cicadas were broken into broods during North America's interglacial period. Much of the middle United States was dominated by glaciers for extended periods. The cicada populations contracted and expanded into different glacier refuge areas, places of suitable habitat that the insects could use during these frozen times. The glaciers would have divided broods from each other, allowing them to continue to evolve separately, one of the reasons why we have periodic cicadas with different clocks, one at seventeen years, and one at thirteen.8

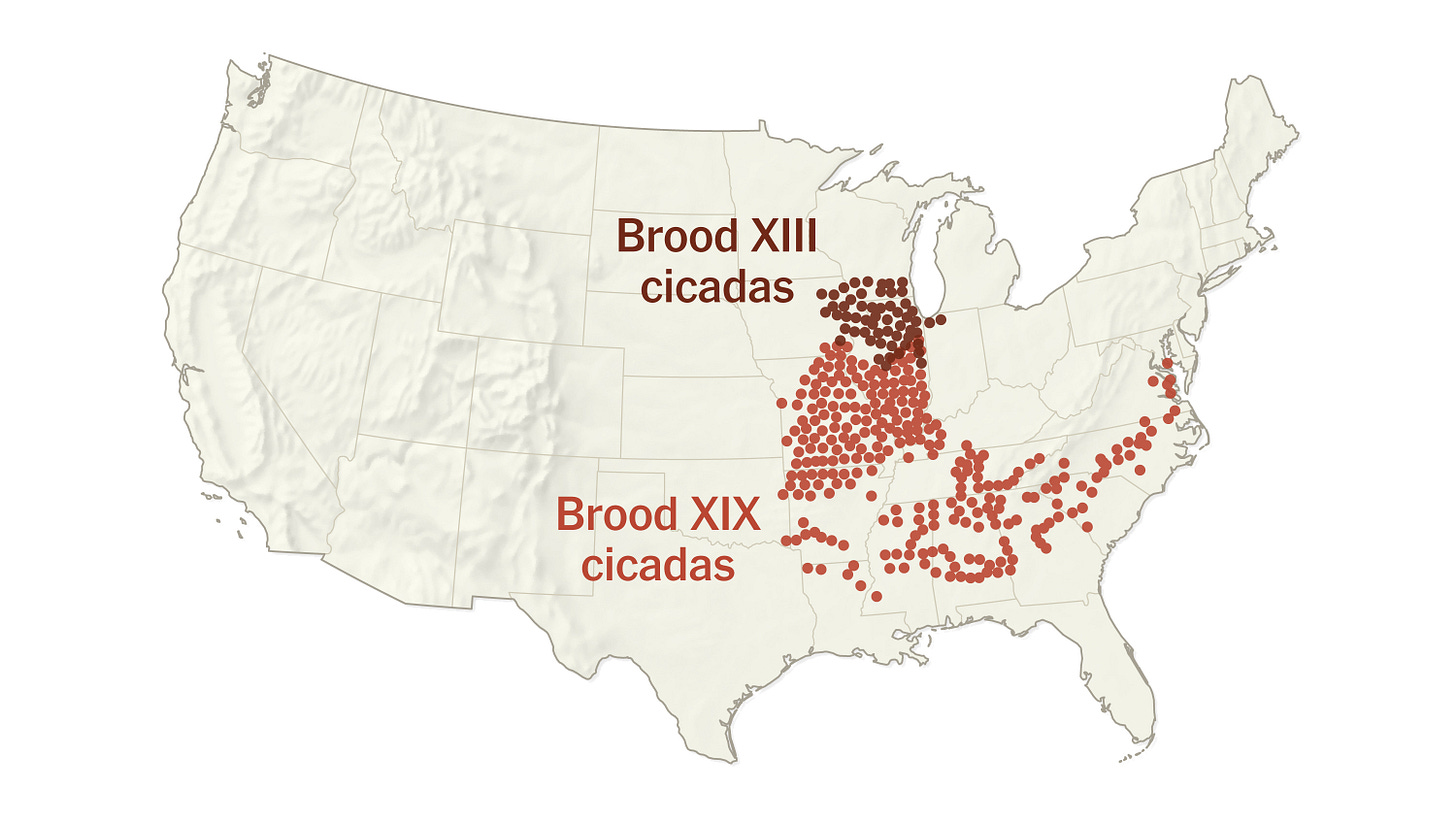

This year, in 2024, we are set to see 13-year broods and 17-year broods co-emerge. This is the first time it has happened since 2015, and the first time since 1998 that neighboring 13-year and 17-year broods will emerge together.

So will there be double densities of cicadas?

Not really. Habitats have upper limits of how many nymphs they can support. Remember, nymphs are eating underground, suctioning the xylem from the roots of the trees. Competition for resources like food and space does limit how many cicadas can be in a forest at any one time. Broods don't often overlap too much, and where they do, there is still a limit of habitat support. Woods can't support double amounts of cicadas.9

So instead of seeing more cicadas in one place, we will see more places with lots of cicadas.

So instead of seeing more cicadas in one place, we will see more places with lots of cicadas.

So more people will get the opportunity to think about this meme:

On the subject of people dealing with suddenly screaming trees, I remembered that I'm a historian. So I went looking for historical data. It turns out that we do have a historical record of the first time the English pilgrims at Plymouth encountered the periodic cicadas! William Bradford, governor of Plymouth, wrote this:

"It is to be observed that, the spring before this sickness, there was a numerous company of Flies which were like for bigness unto wasps or Bumble-Bees; they came out of little holes in the ground, and did eat up the green things, and made such a constant yelling noise as made the woods ring of them, and ready to deafen the hearers; they were not any seen or heard by the English in this country before this time; but the Indians told them that sickness would follow, and so it did, very hot, in the months of June, July, and August of that summer."10

We can see here both the reaction of the pilgrims, but also that the Wampanoag people had retained the memory of a plague that followed the cicadas after their emergence seventeen years ago.

This may have been something like the Diné or Navajo people experienced due to a different kind of resource pulse in 1993. In that year, there was a bumper crop of pine nuts, the product of copious rains. This led to an increased mouse population. The mice carried hantavirus and the humans got sick. Navajo surgeon Lori Arviso Alvord wrote, "It was not the mice, nor the virus per se, that was at fault. Ask the medicine men. They’d known all along how life had fallen out of balance. It was the rain.”11

But while the cicadas were a bane to the Wampanoag and the pilgrims at Plymouth, they were a saving grace for another Indigenous nation.

Over one hundred years later, the Haudenosaunee people (also known as the Iroquois, People of the Longhouse, or People of the Six Nations) were at the mercy of another type of plague.

Only two years after America declared Independence from Britain, George Washington unleashed his soldiers on the peoples of the Six Nations; the Mohawk, Oneida, Tuscarora, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. The Mohawk were closest to the colonies, and settlers continued to encroach upon land that had been set aside for the native people. Angered by the Mohawk's attacks and the removal of the settlers, Washington ordered Major General John Sullivan to carry out an act of unnatural warfare. He wrote this about his plans:

“The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of [Haudenosaunee] settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more... But you will not by any means listen to overture of peace before the total ruin of their settlements is effected...Our future security will be in their inability to injure us the distance to which they are driven and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire..."12

But you will not by any means listen to overtures of peace before the total ruin of their settlements is effected.” -George Washington to John Sullivan

In a military operation that became known as the Sullivan campaign, the forces of the American army laid waste to the Six Nations People, targeting any weak point; crops, homes, women, children, and elderly.

"But the Onondaga survived the attack, the homelessness, the extreme winter, and hunger to try to rebuild a village with very little resources. As the Onondaga struggled to feed its survivors, the Creator sent a gift to our village, Ogweñ•yó’da’ (the cicada). Thousands of cicada came and provided a much needed food source to help the Onondaga survive that first year of rebuilding."13

We see here a different reception of the periodic cicadas. In this case, the year after the Sullivan Campaign caused untold suffering, the Onondaga people were able to survive due to the periodical cicada emergence. The cicadas showed up exactly when the native resources were gone, and to this day, the periodical emergence is celebrated as a sacred, life-giving event that saved their people from further hardship and death.

But it begs the question:

What do cicadas taste like?

Cicadas are eaten the world over. According to those that eat them most, they are best just after their final moult. When the cicadas nymphs emerge, they must still shed their skin to attain their final adult form. They climb up the nearest tree or structure, and there shed that final layer.

Fresh out of their nymphal skins, they are milky-white with a pliable exoskeleton that darkens and hardens over the next several hours. Sources say that they are best harvested and tastiest during this teneral phase when they are still soft and white.

Pop them into the freezer to humanely kill this eco-friendly source of proteins and minerals, then you can boil or cook them at your leisure. You can eat them in a stirfry, battered in tempura, or use them in Cicada Pad Thai.

Rumor has it that they taste like almonds.

However, if you have a shellfish allergy, you should not eat cicadas. The allergen tropomyosin which is found in shellfish is also found in many insects, cicadas included.14

Cicadas don't just make it into dishes all across the world, they also make it into our stories and collective consciousness.

Our most complete stories are from the Greeks:

The first is transmitted to us by Plato.

"The story goes that the cicadas used to be human beings who lived before the birth of the Muses. When the Muses were born and song was created for the first time, some of the people of that time were so overwhelmed with the pleasure of singing that they forgot to eat or drink; so they died without realizing it. It is from them that the race of the cicadas came into being; and as a gift from the Muses, they have no need of nourishment once they are born. Instead, they immediately burst into song, without food or drink, until it is time for them to die. After they die, they go to the Muses and tell each one of them which mortals have honored her. To Terpsichore they report those who have honored her by their devotion to the dance and thus make them dearer to her. To Erato, they report those who honored her by dedicating themselves to the affairs of love, and so too with the others Muses, according to the activity that honors each. And to Calliope, the oldest among them, and Urania, the next after her, who preside over the heavens and all discourse, human and divine, and sing with the sweetest voice, they report who honor their special kind of music by leading a philosophical life. There are many reasons, then, why we should talk and not waste our afternoon in sleep."15

Another Grecian story goes that Eos, the goddess of the dawn, was in love with a mortal, a human man named Tithonus of Troy. So obsessed with her mortal companion and unable to imagine living without him, she goes to Zeus and begs the god to make her love immortal. Zeus does. However, Eos forgot to ask Zeus for the crucial gift that makes immortality bearable: the gift of eternal youth. So as a result, she doomed Tithonus to age for all eternity, sinking into a toothless, creeping old man who sought nothing more than the escape of death. Because the gods never take back their gifts, Eos did the only thing she could imagine, she changed Tithonus into a cicada, so he could complain for all eternity.16

Our final story from the Greeks is from the historian Timaeus from his history about the Island of Sicily. He wrote about two regions, Locria and Rhegium, and they were divided by a river. In Locria, the cicadas would sing, but in Rhegium, they were silent.

(Some say it was because the Rhegium cicadas had annoyed Hercules while he was sleeping and he prayed that they would lose their voices.)

This divide between singing and non-singing cicadas led to a rather fantastic story about two lyre players who entered a musical contest. The musician from Rhegium thought he should win the contest because his family came from the region where the contest was held, and he felt entitled to their familial support. However, the Locrian musician roasted the man, saying that he shouldn't even be able to touch a lyre because, among the Rhegium, not even the cicadas could sing. The Rhegium man was infuriated and began to play with great passion--and the two played back and forth, neither able to top the other. But at the most crucial moment, the Locrian musician's lyre string broke, but a cicada landed upon his lyre and sustained the final note of the man's music, winning the Locrian musician the contest and the glory.17

The world over, cicadas have been regarded as a symbol of resurrection and new life. Chinese dynasties carved jade cicadas and placed them on the tongue of the dead, hoping it would confer the virtues of rebirth to the recipient. Cicadas were idealized; they drink pure dew and transfer easily from one stage of life to another, like the deathless immortals.18

The Aztecs, too, carved jade cicadas and placed them with their dead. Greek and Asian dynasties cast cicadas in gold and wore them on headdresses. Cicadas captured the imaginations of all those who watched them emerge from the ground, cast off their form, and create something new from their own bodies.

Whether or not cicadas can help us transfer more easily to the next world, we do know that their presence makes this present world better.

Their holes aerate our soil, allowing for water and air exchange and increasing its health. Their bodies will feed countless broods of baby birds and forest populations at a time when biodiversity is in peril. Their eggs and nymphs will continue to feed birds and voles throughout the year and the next sixteen.

And when they die, having completed this great work, their bodies will break down to feed the microbial and mycelial life, and the very trees and plants that their nymphs drink from underground. The ecological impact of the periodical cicada cannot be understated.

So in the next few weeks, when you're tempted to pray like Hercules for the cicadas to be quiet, maybe it will help to think of them as singing a song that we can only hear once every seventeen years. Like the totality of the eclipse or the Great Migrations, this is a mystical, precious time for us and the environment.

I'll leave you with the words of Onondaga tribe member Dehowähda•dih:

My father was fortunate to hear their song five times and was thankful every time they came back. So this summer when we go out in the early morning to pick cicada for a treat, it is important to remember how grateful we are for the [Cicada] that was sent to us in 1780 to help us carry on today.19

May we all live to hear the cicadas again in seventeen years.

(Now a message from our sponsor: Hi, it's me, Shay, author of above. Just a quick message that I am a budding Church historian in grad school with a mission to bring academic subjects into wider conversation. If you'd like to support my work and ongoing journey, I would love it if you would subscribe. If you find my work helpful, you can upgrade to a paid subscription through Substack to help buy me a book or two for class, or tip me at the PayPal button below. Thanks!)

Shetlar, David J., and Jennifer E. Andon. "Periodical and 'Dog-Day' Cicadas." The Ohio State University Extension. April 1, 2015. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/ENT-58.

Bartram, Moses. "Observations on the Cicada, or Locust of America, Which Appears Periodically Once in 16 or 17 Years. Communicated by the Ingenious Peter Collinson, Esq." In The Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politicks, and Literature, for the Year 1767, 103-106. London: Printed for J. Dodsley, 1768. https://books.google.com/books?id=k5lGAAAAcAAJ.

University of Illinois Extension. "Cicadas." Accessed May 21, 2017. https://extension.illinois.edu/insects/cicadas.

Nahirney, Patrick C., Jeffrey G. Forbes, H. Douglas Morris, Susanne C. Chock, and Kuan Wang. "What the Buzz Was All About: Superfast Song Muscles Rattle the Tymbals of Male Periodical Cicadas." The FASEB Journal (2006). First published October 01, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.06-5991com

Purdue University Chemistry Department. "Noise Comparisons." Last modified February 2000. https://www.chem.purdue.edu/chemsafety/Training/PPETrain/dblevels.htm.

Yang, Louie H., Justin L. Bastow, Kenneth O. Spence, and Amber N. Wright. "What Can We Learn from Resource Pulses." Ecology (2008). First published March 01, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0175.1.

Charles University Faculty of Science. "Exploring the Evolution of Cicadas Preserved in Amber." Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.natur.cuni.cz/eng/aktuality/exploring-the-evolution-of-cicadas-preserved-in-amber.

Wang, Kuan, et al. "Insights into the Evolutionary Trajectory of Cicadas." Scientific Reports, vol. 5, no. 14094, September 2015. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep14094

University of Connecticut. "The 2024 Periodical Cicada Emergence." Periodical Cicada Information Pages. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://cicadas.uconn.edu

Morton, Nathaniel. "1633." In New-England's Memorial: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America, edited by John Higginson and Thomas Thatcher, 116-118. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Printed by S. G. and M. J. for John Usher of Boston, 1669. https://archive.org/details/newenglandsmemor00morton/page/116/mode/2up.

Cohen, Matt. "The Indians Told Them That Sickness Would Follow: A Response to Miraculous Plagues." The William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 4 (October 2013): 827-831. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.4.0827.

Washington, George. "From George Washington to Major General John Sullivan, 31 May 1779." Founders Online, National Archives. Last accessed May 6, 2024. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0661.

Dehowähda•dih and the Onondaga Nation. 'Ogweñ•yó'da' déñ'se' Hanadagá•yas: The Cicada and George Washington.' May 14, 2018. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.onondaganation.org/blog/2018/ogwenyoda-dense-hanadagayas-the-cicada-and-george-washington.

Illinois Extension. "Considering Eating a Periodical Cicada?" Commercial Fruit and Vegetable Growers Blog, February 20, 2024. https://extension.illinois.edu/blogs/commercial-fruit-and-vegetable-growers/2024-02-20-considering-eating-periodical-cicada.

Plato. "Phaedrus." In Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper, translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff, 535-536. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997.

Deutsch, James. "Cicada Folklore, or Why We Don’t Mind Billions of Burrowing Bugs at Once." Smithsonian Folklife Magazine. May 17, 2021. https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/cicada-folklore.

"Your Cicadas Don’t Sing." Sententiae Antiquae, June 22, 2016. https://sententiaeantiquae.com/2016/06/22/your-cicadas-dont-sing/.

"Khan Academy. 'Cicada.' Khan Academy. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/imperial-china/han-dynasty/a/cicada."

Dehowähda•dih and the Onondaga Nation. 'Ogweñ•yó'da' déñ'se' Hanadagá•yas: The Cicada and George Washington.'